Editor's Choice

Not sure where to start? The African American Communities team have chosen some of their favourite documents from the collection.

African American and Jewish Relations

Cai Parry-Jones

The history of African American and Jewish relations in the United States is a long and complex one. Comprising both periods of cooperation and conflict, it has become a popular area of historical research since the 1970s. Historians have examined the involvement of Jewish merchants in the slave trade as well as anti-Semitism within the black community, for instance. But perhaps the most significant area of historical enquiry was the involvement of Jews in the Civil Rights Movement, which culminated in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Jewish support for the African-American Civil Rights Movement began in the early twentieth century when a number of American Jews became active in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (established in 1909). Henry Moskovitz, a Romanian-born Jew, was a co-founder of the organisation, for example, while New York-born Jew, Joel Spingarn, served as chairman of its board from 1913 to 1919 and president from 1930 until his death in 1939.

The reasons  behind Jewish support of black causes were multifaceted, but they primarily stemmed from both a shared history of suffering under slavery (although Jews participated in the Atlantic slave trade, they were enslaved by the Ancient Egyptians) as well as their own experience of racial hatred, religious persecution and inequality in Europe.

behind Jewish support of black causes were multifaceted, but they primarily stemmed from both a shared history of suffering under slavery (although Jews participated in the Atlantic slave trade, they were enslaved by the Ancient Egyptians) as well as their own experience of racial hatred, religious persecution and inequality in Europe.

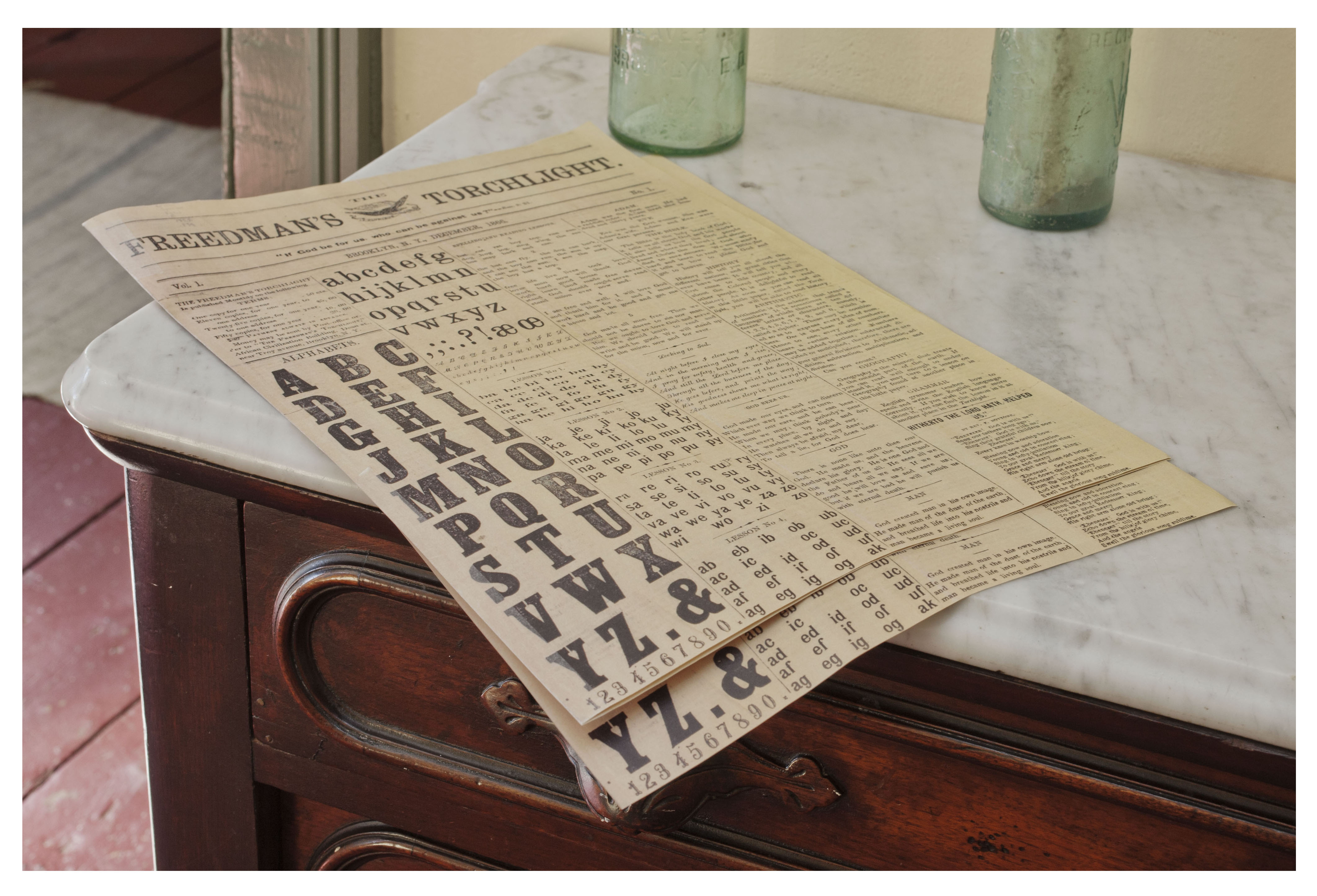

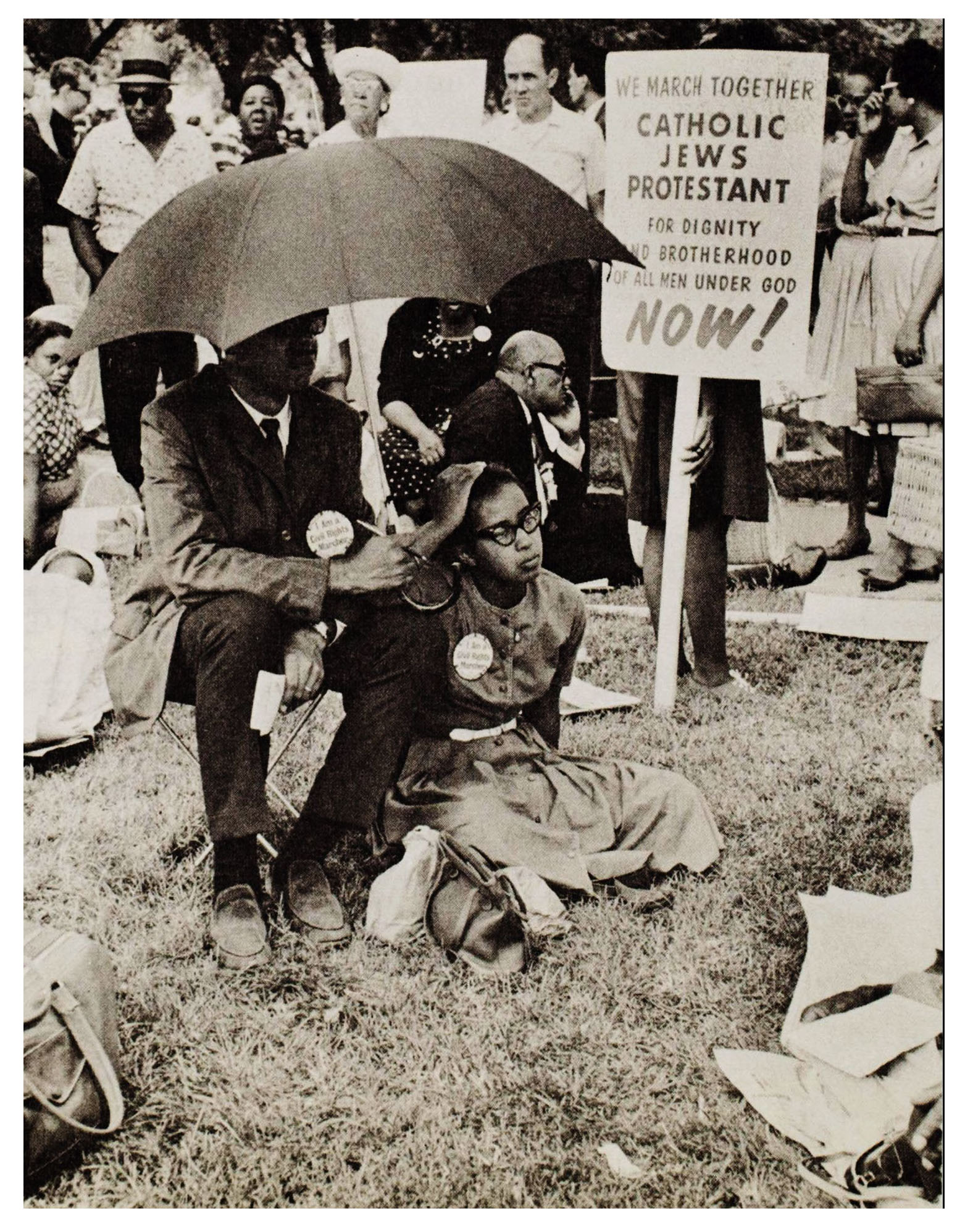

American-Jewish support for black civil rights in the United States increased tremendously after the Holocaust, the state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million European Jews between 1941 and 1945. American Jews funded and led many national civil rights organisations, for instance, and one of their most famous figures was Rabbi Joachim Prinz. A German-born Jew, he settled in the United States in 1937 and devoted much of his life to the civil rights of African Americans, which derived from his own experience of racial inequality and persecution under Hitler. As the then president of The American Jewish Congress, he represented American Jewry at the 1963 civil rights march on Washington, where he spoke of a shared empathy between Jews and Blacks, ‘born of our own painful historic experience’, and encouraged the crowd to speak up against racial inequality and avoid becoming bystanders.

The examples above highlight a few aspects of American Jewry’s engagement with the African-American Civil Rights Movement. Further documents in this resource, including a letter from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) supporting the dissolution of white supremacy movements in the United States and a civil rights report produced by the American Jewish Congress, also attest to this cooperation.

Use the keywords ‘Judaism’ and ‘anti-Semitism’ to discover more documents on African American–Jewish relations.

Support for Educational Segregation

Hayley High

One of the key themes of the African American Communities collection concerns the fight for civil rights and black power. One aspect of this fight was the desegregation of public services such as transport and schools. The collection contains items which highlight both sides of the argument; those who fought to end segregation, and those who were vehemently against integration.

The papers of Herbert T. Jenkins, Chief of Police in Atlanta during the civil rights years, contain many newspaper clippings, speeches, pamphlets and reports concerning segregation in Atlanta and provide an insight into how strongly people felt about this issue. Some of the most surprising items are those which put forward arguments against the desegregation of public schools.

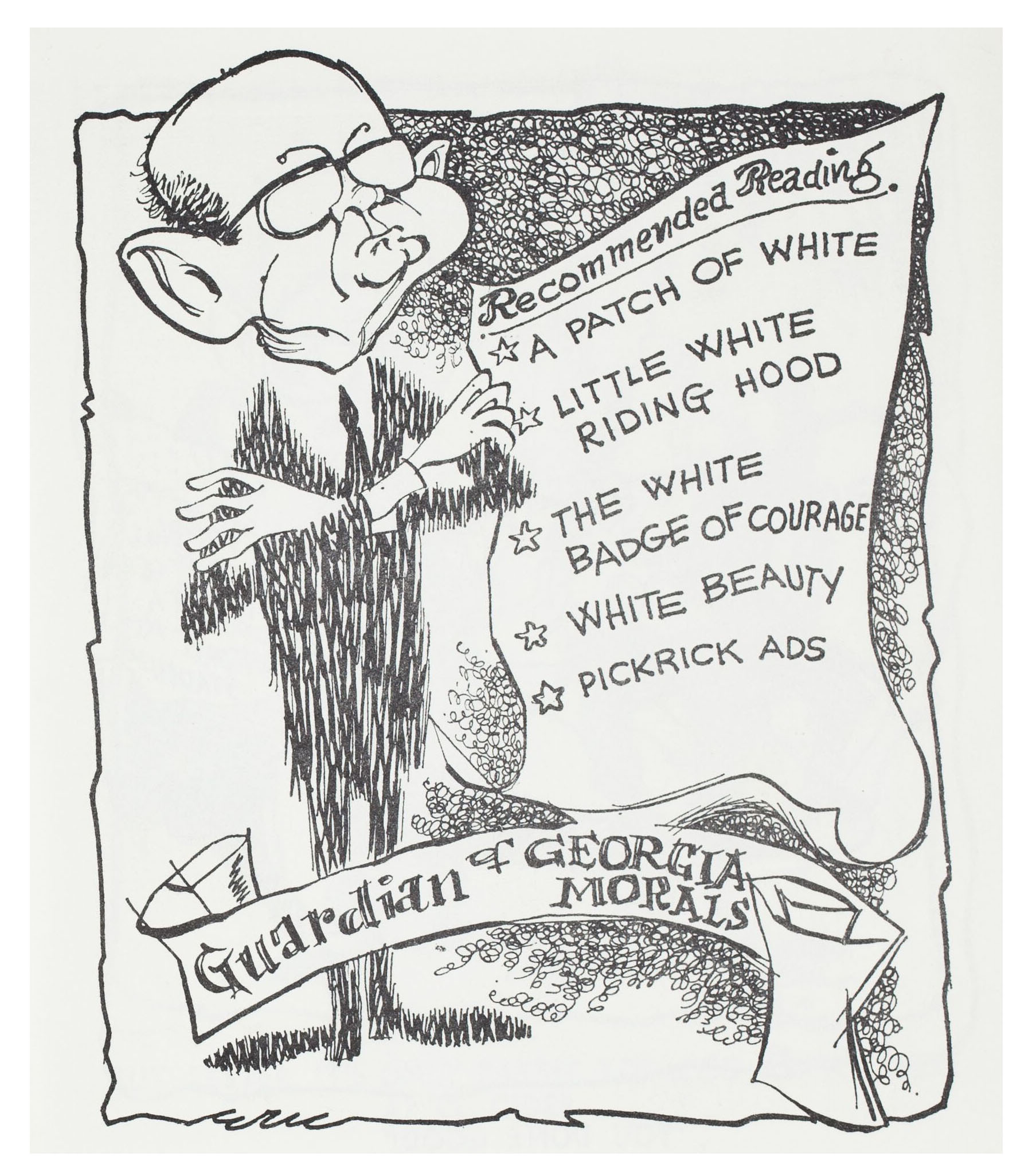

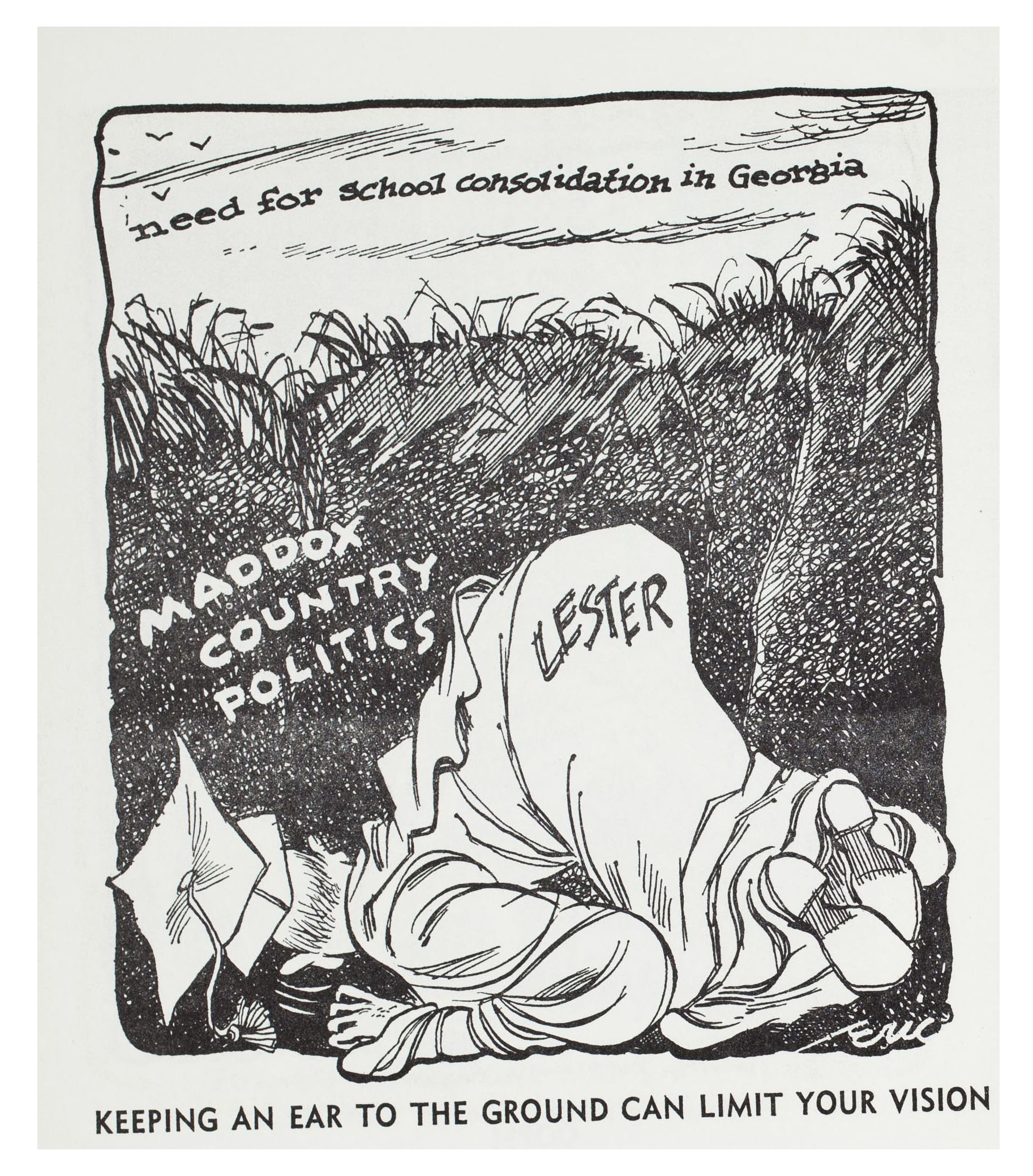

Some politicians actively campaigned to keep the country segregated on racial grounds, for example, Lester Maddox, Governor of Georgia, 1967-1971. Maddox was well known for his segregationist stance and famously refused to serve black customers at his restaurant after the Civil Rights Act had been passed.

His belief in segregation, especially in relation to schools, is highlighted in political satirist Lou Erikson’s booklet entitled ‘This is Maddox Country - cartoon commentary on Lester Garfield Maddox’.

His belief in segregation, especially in relation to schools, is highlighted in political satirist Lou Erikson’s booklet entitled ‘This is Maddox Country - cartoon commentary on Lester Garfield Maddox’.

Little Rock in Arkansas was a hub of activity both for and against the desegregation of schools. One organisation which protested against the  integration of pupils at a Little Rock school was the ‘American Nazi Party’. Overcoming the initial surprise at finding a political organisation in America using this name, it is perhaps hardly surprising that a party espousing the ideals of Adolf Hitler would be against the racial desegregation of the country’s schools.

integration of pupils at a Little Rock school was the ‘American Nazi Party’. Overcoming the initial surprise at finding a political organisation in America using this name, it is perhaps hardly surprising that a party espousing the ideals of Adolf Hitler would be against the racial desegregation of the country’s schools.

The Capital Citizens’ Council (CCC) of Little Rock, Arkansas, also fought against the US Supreme Court’s decision to desegregate schools; focusing on the Little Rock Central High School. When nine black school children attempted to enrol in the school, the protest marches made by anti-integration supporters, and the subsequent violence, made national and international news. These nine students were initially removed from the school for their own safety, unable to return for several weeks until soldiers were sent to guard them in their classes.

The CCC created pamphlets within which they re-published newspaper articles from other publications in an attempt to warn the people of America of the dangers of integration.

In the extract below the Council uses the front page of the Chicago Defender, which depicts a prominent black female member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Mrs Daisy Bates’ with several white teenagers who are attending a mixed summer camp to champion the integrationist cause. The Council points out that at least one of the white people in the picture is a recent graduate of Little Rock High School and warns that if the integrationists are successful “pictures of this type will soon become commonplace right here in Little Rock. Next year it could be an interracial class picnic at Boyle Park!”

The African American Communities collection reveals that the anti-integration stance was held by various different types of people, groups and organisations. The collection tracks the progression, and ultimate success, of the desegregation of public services and further aspects of the civil rights movement.

'A black man's disorder': The 'appropriate paranoia' of African Americans

Sara Hussain

Working on African American Communities has given me a new appreciation for the lives of those I had previously mainly studied only from a civil rights point of view. This collection not only allows one to gain insight into their daily lives, but through each aspect the greater struggles that they faced so often are always brought into sharp relief.

There was much research being done into the specific health needs of African Americans; for example, it was found that they were more susceptible to the sickle cell trait and the associated sickle cell disease. This attention, however, could be both good and bad, as this demographic and these health issues became conflated, so that sickle cell disease came to be seen as “a black man’s disorder”. This general lack of understanding amalgamated with the prejudice some felt towards African Americans to create a new discussion concerning the ethics of genetic screening. It was feared that legislation for such screening would lead to new reasons for some to discriminate against Africans Americans, such as those in the army who could be relieved of their duties if found to have the sickle cell trait. Dr. Gerald E Thomson of Harlem Hospital summed this up well, quoted in an article from the New York Post of 18 Aug 1973: “…it was amazing, as if medicine had discovered a new disease. Then there was a tremendous emphasis on screening for the disease- then on screening for the carrier state, which is probably not a disease at all. Then a byproduct of screening legislation shows up in the attitude of insurance companies and employers. Rates go up. People have been fired. The Air Force rejects recruits".

This one example is part of a wider context which shows how African Americans interacted with the health sector. In essence, they had what Dr. Thomson termed “an appropriate paranoia”, as questions of their health could so easily play into wider prejudices levelled against them. The African American community wasn’t entirely composed of patients, of course; black physicians also had their role to play: ‘He’s got to recognize when the drug companies are ripping off his patient. He’s got to be involved in the politics of his community. He’s got to watch for legislation that affects his patients. He’s got to be a social advocate’.

Clearly, there was a great disparity between African Americans and their white countrymen where health was concerned. In the ‘Position Paper of People’s Health Council for First Third World People’s Health Conference of the West Side’, it is revealed that ‘our people’s lives are 10 years shorter than whites’. Barbara Yuncker’s aforementioned article breaks this down further still: ‘American blacks are about a tenth more likely to die of cancer than whites. Their women are four times as likely to die in childbirth, three times as likely to bear a dead infant. Black women with diabetes are blinded three times as frequently by its late effects as are whites. The list goes on and on’.

The list may have been long, but the issue of health amongst the black community was something of a catch-22 situation where their difficult socioeconomic conditions led to many health complications but which also precluded them from getting the care they needed. Another African American physician, Dr. LaSalle D Leffall, Jr eloquently broached this subject when questioned:

Explore the Chicago Urban League (CUL) papers or use the keyword ‘health’ to discover more about this topic.

I'll Make Me a World

Sarah Hodgson

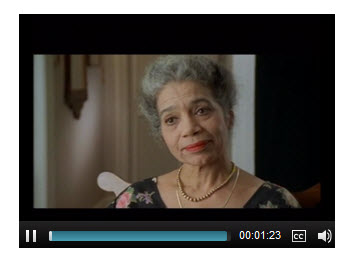

One of my highlights from African American Communities is the oral history collection ’I’ll Make Me A World: African-American Artists in the 20th Century’ from the Henry Hampton Collection at Washington University in St. Louis. The collection celebrates the extraordinary achievements by influential African American artists of the 20th Century.

One of the interviews in the collection is with Raven Wilkinson; a ballet dancer and the first African American woman to dance full-time with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in the mid-1950s. Wilkinson talks us through her life as a young girl and her love for dancing:

One of the interviews in the collection is with Raven Wilkinson; a ballet dancer and the first African American woman to dance full-time with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in the mid-1950s. Wilkinson talks us through her life as a young girl and her love for dancing:

‘You are an instrument just like a singer is an instrument, or a violin, to express that music. And I guess it's just a joy to be able to do it. I don't know what draws us so, but when we are drawn, we are very much dedicated.’

Wilkinson describes auditioning for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo and describes the ‘glass wall’ for African American women in ballet at the time. Wilkinson was accepted into the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in 1955 but explains in the interview that she was accepted on a trial basis because the company were touring the Southern states of America for the first 6 weeks of shows. The Jim Crow laws, upheld in the Southern United States until 1965, prohibited businesses from permitting social functions including dancing and entertainment where the participants were white and black. As soon as the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo reached Chicago Wilkinson became a member of the company. Wilkinson describes her experiences in the Southern states including an incident at a hotel where she was asked to leave by the hotel staff:

"And the man who is the manager of the hotel came over to me and said, that they'd asked my company manager if they had a Negro in the company and he had said no. And he said, but they gotten the black elevator operator, who was a woman, to identify me and she thought I was black, a Negro at that time. And I said, well yes I am. And he said, well, you know, you can't stay here, it's against the law … And so they called a colored taxi and I took a colored taxi and went to a colored motel."

Wilkinson goes on in the interview to talk about her experience with the Ku Klux Klan, her disappointment when the company deemed it too dangerous for her to perform in the Southern states and life after the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Wilkinson’s interview is so interesting to listen to in a time where many of world’s elite ballet companies are still criticized for their failure to cast black dancers. Replying to a question about being labelled a black artist Wilkinson responds:

‘I think an artist, primarily, is what it says it is. It's neither black nor white, it's an artist communicating their spirit, their soul, their conception of the world to people.’

For a full listing of the oral histories included in this resource please click here.

Sweet Home Weeksville

Sarah Madsen

While working on African American Communities, I found the Weeksville Heritage Center archive to be of special interest. The collection invites you to step into a completely different era and really see what it meant to live and work as an African-American in the neighbourhood of Weeksville. From the perspective of the historian or scholar, it is easy to understand the significance placed on houses and personal belongings in the study of the past. An exploration of buildings and the objects within can offer not merely a glimpse, but rather a detailed and intimate insight into the everyday lives of the people who lived and breathed in the moments that we now call history.

Weeksville, a neighbourhood founded by an African-American freedman in 1838, is a wonderful example of a place defined by its creation. The building of each and every house signified the promotion of racial respectability and the beginning of a thriving free black community, where African Americans could live and work as craftsmen, entrepreneurs and professionals. As the popularity of Weeksville grew, it became sought after as a place of refuge for people either fleeing slavery, or escaping racial violence. Weeksville again became a safe haven for African Americans fleeing Manhattan during the violent New York City Draft Riots of 1863. Today, following extensive restoration work, Weeksville exists as a representation of the houses that were once inhabited: The Historic Hunterfly Road Houses, as shown in the image.

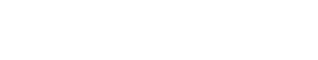

It has been a privilege to explore a collection that until not long ago was part of a lost community. The uniqueness of the collection has to be in its raw representation of daily life, from the tough leather shoes worn by a labourer, to some ‘Penn’ candles which presumably adorned a birthday cake. While the beauty of the collection lies in its simplicity, much can be gleaned from the vast variety of original objects found within. One particular mantelpiece displays personal family photographs, accompanied by a hand-coloured lithograph of ‘Distinguished Colored Men’ where Frederick Douglass, an African-American social reformer and former slave, takes centre stage. Further exploration reveals the ‘Freedman’s Torchlight’, one of the first African-American newspapers to be published, lying on a chest of drawers.

A fantastic addition to the collection is the Weeksville interactive exhibition, which encourages the user to freely explore the various rooms and objects at their own pace.

As a case study, Weeksville sits perfectly within a resource that explores race relations across social, political, cultural and religious contexts. It is incredible that a mere eleven years after the abolition of slavery an entirely African-American neighbourhood was created, and it is perhaps the conception of Weeksville that serves to reinforce its identity as a place that should never be forgotten.